Originally published on Singal-Minded and now unlocked for everyone. If I’m allowed a moment of narcissistic vulnerability, re-reading the last paragraph always makes me cry.

“Where are you from?”

It’s a question leveled at me often, and one that I tend to find annoying because it’s asked in such an awkward and ambiguous manner. For example, on the first day at an internship, my cubicle neighbor came up to introduce herself. She was a white middle-aged woman, and she looked at my nameplate and slowly formed a question: “Yassine… that’s an interesting name. Do you… happen… to know… what your… cultural… heritage is?”

I had to laugh at how stilted her language was, but I knew what she was getting at. She saw my name (or my swarthy complexion, or both) and wanted to know my origin story, which is cool. Usually for this type of vague question, I play dumb and say something like “Virginia” just to see the asker’s look of exasperation. But I can give straight answers if I’m feeling earnest or if they ask more directly. Where am I from? No, really, Virginia. Where am I from before that? Ah, well, I was born in Morocco if that’s what you’re asking. How did I get here from Morocco? I won a lottery.

Seriously. The only reason I live in the United States is because I won a lottery.

Morocco is in North Africa, one side of the entryway to the Mediterranean basin, and separated from Europe by a mere seven miles of water. Morocco’s peculiar geographic positioning is reflected in its endless layering of historical strata — it has served as an ancient frontier of the Roman Empire, stepladder for the Islamic conquest of Iberia, and a French and Spanish colony.

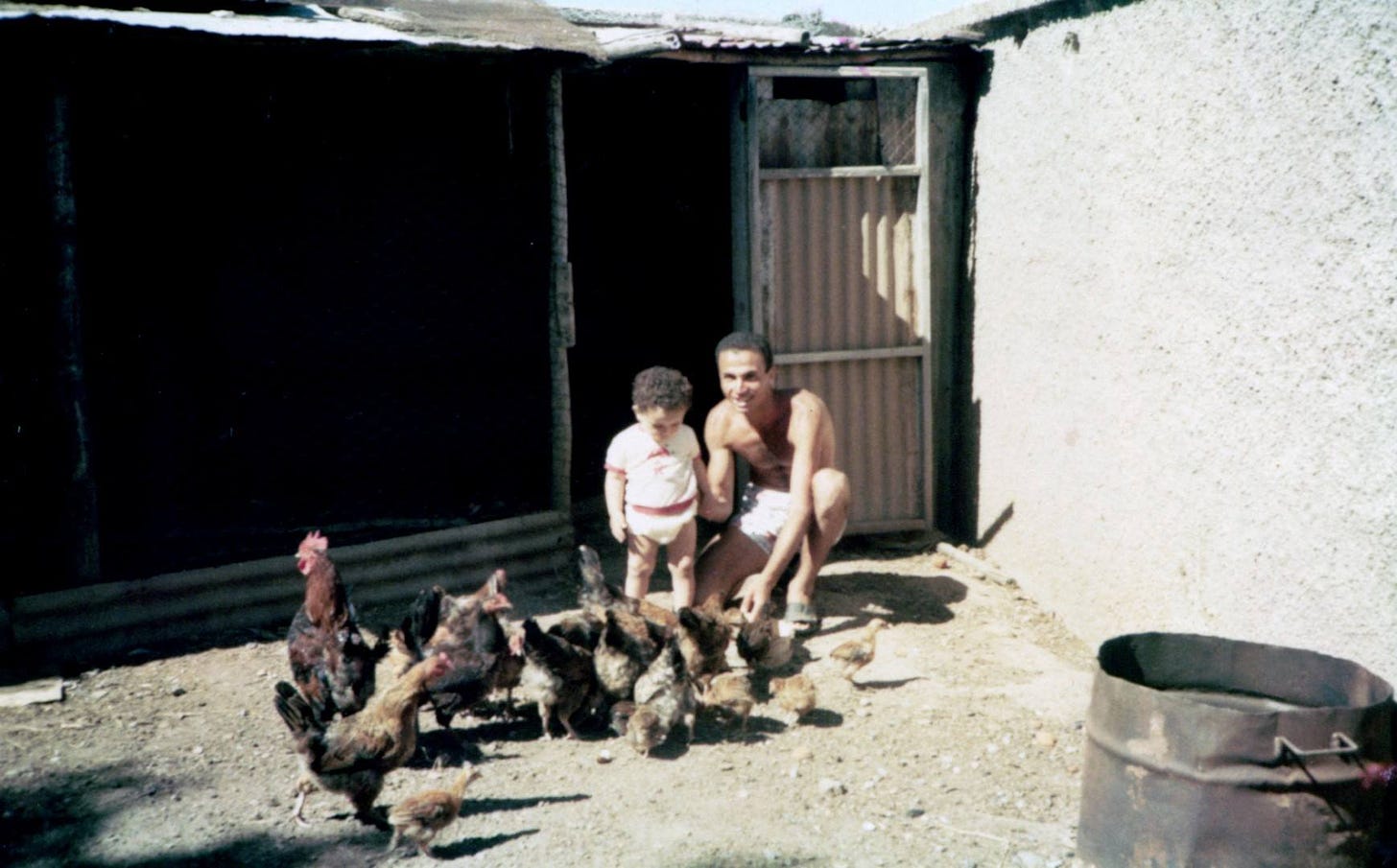

Morocco is where I was born and where I spent my formative years.

Sitting at the cultural crossroads among so many big players, we had our fill of media to consume, but all of it struggled to compete against the overwhelming juggernaut of American Cool. Disney characters were everywhere (the colloquial word for cartoons in Arabic is Mickey-yat), and I read through Le Journal de Mickey and other comics every week. We were all obsessed with Michael Jackson, of course, and the only music out of Europe we listened to were techno groups like Snap! and the rest of the German/Belgian scene — bands that donned thoroughly convincing American cosplay. Our elders tried to encourage us to watch the respectable oeuvre of the Egyptian silver screen, but how can any of that compete with the adrenaline injection that is Terminator 2? It was surreal to think a single country, far across the horizon, could be the source of all this.

Although the average income in Morocco is about a tenth that of the U.S., my family was fairly well off by home standards. Both my parents went to college (unlike any of my grandparents), and both were able to study English abroad as they went on to attain graduate degrees. They were rewarded with cushy teaching jobs and full summers off.

We’d often use those summers to jet across the Atlantic to spend a couple of months with my aunt, who lived in Virginia.

America was already a formidable presence as a distant idea. But when I visited in person, it was downright magical. This was before I hit puberty, so during my visits I was obsessed with two things in particular.

The first was Cartoon Network. In Morocco, we had only two TV stations — the first (literally called The First) was the Plain Jane free-to-air public option, while the other (creatively titled 2M) required an entire decoder box. That’s it, though — two choices. So imagine my delight when I visited America and found that some homes had access to hundreds of TV stations, and that several were entirely dedicated to cartoons. Heaven.

And then the second thing, the crowning achievement of American hegemony: McDonald’s. Morocco had one McDonald’s at the time, and it opened to great fanfare. It was built on a cliff in Casablanca overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, and it also had fucking valet parking. Generally only tourists and bougie Moroccans went to restaurants, and Le Macdo was seen as another tony destination meant to showcase their globalized palate. So when I came to America and noticed they had a McDonald’s on every street corner, I couldn’t help but conclude: America has figured things out. So my life during our American vacations consisted mostly of cartoons and hamburgers.

Then one day in my aunt’s apartment, everything changed. My mom, still in her pajamas, was transfixed by a phone conversation. She noticed me watching her and said, “Yassine, we’re moving to America.”

My exposure to America at that point was as a tourist and a gawker. I had no idea what living here would mean, but my ten-year-old brain tried its best to simulate the scenario. I dug around the archives of my memories, saturated as they were with a trove of material to pull from, and retrieved the image that stood out the most: a school cafeteria. Saved by the Bell was not just a TV show; it was an ethnography.

We didn’t have school cafeterias in Morocco. Instead of eating lunch at school, we’d take the bus back home for the hour and a half break. My parents also had that time off, a standard workplace custom, and we’d eat lunch together and then tune in to catch up on whatever Brazilian telenovela the country was obsessed with at the time. I then went back to school for the afternoon and talked to my friends about how we couldn’t believe that Guadalupe got back together with Felipe despite everything that happened between Esmerelda and Carlos. That’s at least one upside to having only two television stations: national cultural cohesion.

I cast myself within this simulated fantasy as best as I could given my limited knowledge. I saw myself standing in line holding a steel tray laden with [American Food] and next to me was my new [American Best Friend]. I had no other guidance about what to expect, but this seemed nice enough. I looked at my mom and shrugged, vaguely indicating assent.

The phone call that had so engrossed my mother was about a letter from the U.S. Department of State informing us we had been randomly selected for the Diversity Visa immigration lottery. We’d won the lottery.

It’s no surprise if you’ve never heard of this program (also known as the Green Card lottery), even though it’s responsible for bringing 55,000 new immigrants to the States every year. It picks one hundred thousand names at random from the millions of applicants, all of them from countries that historically have had a low rate of emigration to the United States. Most of Asia and Latin America tend to be ineligible as a result, which was likely the original intent behind the program — it wouldn’t be completely unreasonable to consider it the “Too Many Mexicans, Indians, and Chinese” immigration platform. I like to think it’s a giant top hat full of scraps of paper, with someone using a leaf skimmer to scoop out names.

Even if you get lucky and win, there are still myriad logistical hurdles to overcome. The government actually picks far more names than it can process, because only about half make it through the gauntlet. Anyone who does reach the end becomes a permanent resident and can qualify for citizenship. Sometimes applicants abandon the process voluntarily, while others fail to meet the rigorous requirements and unforgiving deadlines.

Years ago, This American Life aired an excellent episode called “Abdi and the Golden Ticket,” which documented in detail just how tense and uncertain the trajectory can be for some lottery winners. Abdi was living in Kenya as a refugee from Somalia when he received the unbelievably good news that he was chosen by the Green Card Lottery. On paper, some of the application’s process requirements are fairly rote and banal, such as securing a certificate of good conduct from local law enforcement. Unfortunately for Abdi, he had to navigate this around the same time a Somali terrorist group, Al-Shabaab, was wreaking havoc around Kenya. Al-Shabaab was already notorious for the 2013 Westgate shopping mall attack in Nairobi, and they continued their campaign in Kenya by targeting buses and police stations with bombs. This sparked severe suspicion and retribution against Somalis living in Kenya, and it was the atmosphere Abdi had to brave as he walked into a Kenyan police station and asked for a signature.

In comparison, my family faced nothing like Abdi’s hurdles, and we benefited from several advantages. Our immigration lawyer was there to guide us through the whole process, and the first piece of advice she gave us was: Stay. If we were really serious about making the U.S. our new home, our best bet was to stay where we were. Had we gone back to Morocco as originally planned at the end of our vacation, we’d be funneled through consular processing at the American embassy there, which is short-staffed and not known for its efficiency. The alternative was to apply for Adjustment of Status and get a direct pipeline to the bureaucratic apparatus. Plus, we’d get to live in America while the paperwork shuffled.

So we canceled our flights back. I never said goodbye to any of my friends, and I wouldn’t see them again for a while.

By this point my English was okay. I’d mostly attained it through incidental absorption. For example, during a trip through the subway with my mom, the station attendant asked me how old I was. I responded with the usual pride expected by my age cohort and excitedly announced, “Six!” My mom immediately intervened, flustered, and assured the attendant, “No no no, he doesn’t speak English and doesn’t know what he’s talking about. He’s only five.” I later found out kids five and younger didn’t have to pay a metro fare.

That type of resourcefulness and corner-cutting served us well, and we hit the ground running in our new country. My dad went from working as an English professor to working at a photocopy center, while my mom went from working as a sociology professor focusing on women’s studies to working the perfume counter at Sears. We moved to an apartment in the suburbs and didn’t have the money for a car. We were floored at the sheer amount of stuff our American neighbors threw away, so we dumpster-dived all the time. That’s how we acquired multiple couches, mattresses (questionable haul, given some of the stains), and televisions. Whatever we didn’t dive for, we accepted as donations or sought in thrift stores. The latter were particularly helpful, as we had packed only for the summer and were unprepared for the rapidly approaching fall. I saw snow for the first time in my life a few months later, utterly mesmerized by how sparkly it was at night.

Before I started school, I was informally tested for grade placement. In a small room, an instructor gave me a choice to read about amphibians or U.S. presidents. I picked team amphibians, and I recounted to the instructor how they lay eggs, crawl on their stomachs, and have smooth skin. Bingo. My next choice was fiction, and I could choose between a passage from Fantastic Mr Fox and who cares what the other option was because I said, “Oh! I read this in French already and it is one of my favorites. I am ready for your questions.” I immediately recounted, in English, how the book is about a sly fox who lives with his family next to some farms and how he builds some tunnels to — they heard enough. I didn’t have to repeat any grade levels. A mere three weeks after we first received the lottery news, I started fifth grade. I finally saw a school cafeteria in person.

A while back I came across a university-issued cultural adjustment guide for foreign exchange students — a fascinating read for anyone already steeped in American culture. For example, it warned against assuming romantic intent when invited to have lunch with someone and cautioned against showing up to dinner parties three hours ahead of schedule, as apparently is the norm in some places, and so forth. But there was no “Welcome to America” PowerPoint presentation when I arrived. I had to figure out all the minutiae on my own.

I had always been a feisty and gregarious little kid who loved telling jokes, and so I was excited to make new friends. It wasn’t so easy. On the first day of class, I showed up with a small Afro and some tight bicycle shorts. My mom’s sense of American gender coding apparently was off, because when I went to the boys’ bathroom, everyone started yelling, “Wrong bathroom! Wrong bathroom!” My new classmates turned that experience into a running joke, and mockingly asked me, “Are you a boy or a girl?” The sartorial ridicule didn’t stop there, as I then made the faux pas of wearing the same clothes two days in a row and was derided as dirty for doing so. Confused by my classmates’ cruelty, I kept a mental map of the best places I could hide during recess (behind the toolshed by the swingset was the best).

As a kid still grappling with normal kid-stuff, the added burden of assimilating to this strange new landscape was deeply isolating. (The best expression of the sentiment of finding yourself thrust into an alien and inscrutable new landscape is the wordless graphic novel The Arrival.) I did my best but inevitably retreated from everyone.

After a whirlwind of a year, we finally went back to visit Morocco and retrieve what we had left. I was able to visit my old school. As soon as my old friends saw me enter the room, they swelled forward to bum-rush me and smother me with kisses. I missed my friends terribly, and I felt genuinely loved in that moment. They asked me if I met any celebrities. I didn’t tell them how mean people were.

You’re reading this now, decades after the events described above. You can reasonably surmise things have more or less worked out given what you know about my station in life. But never forget where it all started. My family did not receive an American Green Card because we worked harder, were more deserving, or otherwise earned it. It was blind fucking luck. Everything that followed was predicated on random chance.

The short old lady who asked me for help reaching a tall shelf at the grocery store last month. The driver whose insurance premiums skyrocketed after he hit me on my bicycle. The father whose life was altered because I happened to invoke the right words in court. The friends I made along the way. The people I learned to love. The smiles I prompted. The crying I instigated. The hugs I gave. The words you are now reading.

All this. All of it. All because a computer picked my name out of a hat.

Yassine Meskhout is a contributing writer at Singal-Minded. You can read more about him here. Questions? Comments? Plea deals? Email him at ymeskhout@gmail.com or me at singalminded@gmail.com.

Beautiful essay! Thanks

I love this.