Public Pretenders

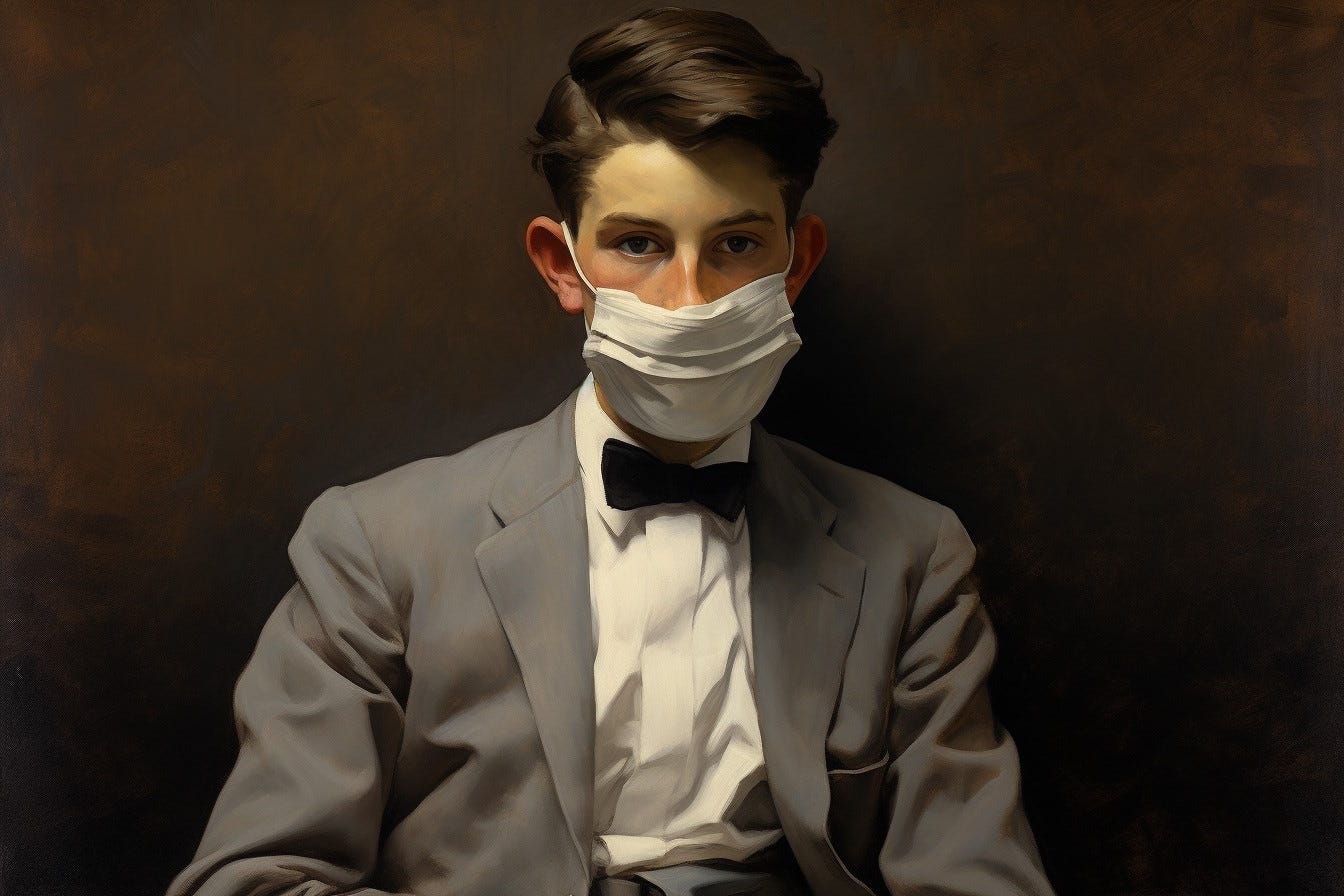

The difference between a public defender and a private attorney can often be measured not in skill, but in pinstripes.

The defendant had dropped a rhetorical bomb in court. He lobbed the grenade of all insults. He called his attorney (may Allah forgive me for repeating this) a public pretender. The courtroom’s sparse decorations afforded plenty of space for the silence to permeate. The room was almost empty as they were basically done with that morning’s calendar. Early too, which meant the judge had some time to fuck around.

The judge adopted the familiar tenor of a police interrogation — the verbal equivalent of a slow-moving suffocation. He turned to the so-called public defender and started asking him questions.

“Mister Weber…did you even go to law school?”

“Yes Your Honor.”

“Well…are you even licensed to practice in this state?”

“Yes Your Honor.”

The judge was hamming it up with the weight of a Shakespearean monologue and the public defender did his best to stifle his laughter, just enough to utter out a coherently monotone answer. The judge continued, savoring every liminal pause for dramatic effect.

“Mister Weber…I need you to answer this next question truthfully…are you — are you a real lawyer?”

This was the final Yes Your Honor, what finally broke the tension. The judge’s demeanor visibly relaxed and he shifted back in his dais. He turned back to the defendant and said “Thank you very much for bringing this serious accusation to my attention, but I am relieved to find out that Mr. Weber is indeed a real attorney and is not just pretending to be.”

Oh yes the defendant was being blatantly fucked with, but the artificial gravitas was a sufficiently plausible deniability shield to keep him guessing. Besides, what the fuck was he going to do anyway? Pull a rhyming dictionary out of his ass and look up another entry for defender? Maybe next time he can come to court prepared with a more original barb than calling his attorney a public pretender.

Make Me Feel Mighty Real

Money is what makes it real. Which is why I, a public defender, am fake as fuck. I am free of charge. I am the budget option. I am also functionally the default.

Choosing to navigate the legal field without an attorney — also known as “rawdogging it” in the parlance1 — doesn’t usually work out very well for reasons I previously wrote about. And yet, the modern public defense system exists entirely because of a handwritten appeal to the Supreme Court scrawled out on prison stationary. Easily history’s most successful pro se filing. Gideon v. Wainwright is why if the government finds itself primed to shove you through the prosecution grinder, they are at least magnanimous enough to give you an attorney. They’ll even go so far as to foot the bill if your ass is broke as fuck. Noblesse oblige is not totally dead!

But how good is this default, really? It’s Complicated™.

Anyone seeking to examine the criminal justice system by comparing public defenders with privately retained attorneys will find themselves stymied by the fact that public defenders basically are the system. Any poor schmuck (notice I didn’t say blameless) unfortunate enough to capture the attention of our nation’s indefatigable law enforcement apparatus is almost by definition financially destitute, and that’s all you need to qualify for the free option. How much of a shit a jurisdiction gives about people [nose scrunched up in disgust] accused of a crime will vary, and this will be reflected in detail within boring public finance documents. But regardless of that variance, courtrooms are brimming with such a glut of indigent defendants that when the BJS looked into this decades ago, they found that roughly 80% of state felony defendants were represented by a public defender. Point at any random spec of meat pushed through the grinder and you can reasonably assume a public defender is chained along for the ride.2

Another confounder is that many public defenders are…private attorneys.3 Some towns are way too small to have a dedicated agency with full-time government employees, so they farm out indigent defense to local attorneys who can periodically step in as needed on a contractual basis. Even big cities with gargantuan public defense departments rely heavily on private attorneys as gravel to fill in the gaps left by conflict of interest recusal (something like an entire agency withdrawing from a case because one of their lawyers had previously represented the victim or something) or just when they’re over-capacity. At the federal level, private attorneys take up about 40% of public defense cases. Every private criminal defense attorney I know takes on public defense cases as a supplement to their paying clients. No need to advertise your services or chase after the inevitable unpaid invoice when the local government takes care of both problems.

The overwhelming majority of criminal defense is not financially sustainable, and would not exist without the constant injection of taxpayer money. The reason for this discrepancy is obvious. Rare is the criminal defendant who has enough of their shit together to afford a defense attorney at market rate. As authentic as Better Call Saul! was overall in its depiction of criminal defense life (and I can’t praise the show enough on that front) the idea that Saul Goodman could financially sustain a criminal defense practice by marketing to the dregs of society was pure fantasy. I once had a client stab a dude in broad daylight, in front of a dozen witnesses, slightly fewer surveillance cameras, and screamed his own name in the process. This is not a dude with the temperament to get a regular paycheck every two weeks. Financial security (either directly or as a confounding variable) also gives you the respectability, influence, and resources to shield any potentially criminal behavior away from the prying eyes of law enforcement. Money is great, and I highly recommend having it.

All this to say that any attorney working in criminal defense is necessarily working with a skewed clientele pot. Without some adroit specialization, there is no cash to wring out of this crowd. The options are limited for carving out a private practice that doesn’t feed at the public defense contract trough. Some freak attorneys do so by launching their stature to the stratosphere, high enough to sustain a steady living off big-ticket celebrity defendants. The more realistic solution is to be selective in your fishing, pursuing only the practice areas most likely to deliver on the narrow Venn diagram slice of “accused of a crime” and “has money”. A reliable eddy for this approach is to be boring as fuck and dedicate yourself almost exclusively to drunk driving cases.

Sartorially Deficient Efficiency Machines

I got my start at a public defense agency and while we did indeed have caseloads stacked high to the ceiling, this doesn’t tell you the full story. For one, the benefits of functionally being part of the system means you can spread some fixed costs across several clients (e.g. handling dozens of clients during a single morning calendar). The other part is that public defenders naturally become machines of raw unbridled efficiency.

You can usually easily tell them apart from their privately-funded aristocratic colleagues. One of the best public defenders I know wears the exact same cringe-inducing blazer to court, with the sleeves nearly a foot too long drooping over his hands like a monk’s robe. He doesn’t give a shit though as he’s pared down his repertoire of tools down to the bones, leaving behind only the things that will actually make a difference for his client’s cases.

The sheer volume of cases also comes with some supernatural scrying abilities. The prosecutor’s office we worked with handled thousands of cases, and they used internal plea deal standards to maintain some semblance of uniformity across the thousands of cases they handled. Their (at times robotic) devotion to fairness chafed at the idea of giving two similarly situated defendants vastly different plea deals. And while they never shared those internal standards with us, all it required was churning through a few dozen cases before the standards became obvious to anyone paying attention.

For DUIs, the biggest factor was blood alcohol concentration. The scale public defenders operated at made it trivial to figure out the BAC threshold for getting a one level reduction in the charges, or even two levels if you were lucky. We also knew which factors could tip the scales for edge cases (Practice Tip: crashing into a trailer home and narrowly hitting a sleeping twelve year-old is Very Bad).

We used a checklist to quickly triage our never-ending DUI caseload. Tell me just a handful of details about a case and I can predict its ultimate conclusion with startingly accuracy. Most of our cases were obvious enough that they were on auto-pilot to a predictable plea deal conclusion, and we could then focus our attention on the edge cases that were most liable to topple over. With the volume of cases I had, the median DUI misdemeanor probably took me maybe two or three hours of work total, including all the time spent in court waiting. This was all boring, tedious, and predictable work.

Besides all that, I got to know all the player’s tics. Jennifer the court clerk was a total sweetheart, and she was the one I should talk to if I need to overset on an already full morning calendar. Brett the prosecutor really did not like repeat offenders, so I continued those cases until he finished his rotation and I had to deal with someone different. And you memorize the judges especially. I had a client who was summoned to court because her drug treatment provider kicked her out for “contraband”. I assumed that meant she brought drugs to rehab, but turns out the “contraband” was just a cell phone. Before the court even knew what was going on, she had re-enrolled voluntarily and completed a month of inpatient treatment. When she told me all this I figured it was a shoo-in for the judge to impose no sanctions. I said “You were proactive, which is something this judge really appreciates. Also, the judge absolutely hates the prosecutor on this morning, so this hearing should be a cakewalk.” Five minutes into the hearing, the judge was yelling at the prosecutor already. My client and I exchanged knowing glances, and she marveled at my divination.

Private attorneys knew we had a finger on the pulse, and we were often asked for input. Sometimes it was something as banal as asking for a temperature check on a judge right before sentencing. By far the most jaw-droppingly alarming was when a client walked into the courtroom about to plead guilty to a DUI. His attorney paused at the door where I happened to be loitering and asked me “Hey my client is a green card holder and he’s going to plead guilty to a marijuana DUI. That’s not a big deal is it?” That could’ve been a catastrophe, to the extent you consider immediate deportation to be a big deal.

America's Universal Crime

There’s a reason DUIs come up frequently in my writing — they’re the bread and butter of misdemeanor criminal court and what virtually all defense attorneys cut their baby teeth on.

Americans love drinking. Americans also love driving. If you're concerned about this concatenation, worry not commie scum because the third branch in this triumvirate is another perennial American favorite: an unrelenting police force. Hands wiped, problem solved.

You have not experienced the unique essence of America until you are drunk as hell at a strip mall parking lot at 2AM, locked out of the Applebee’s that just closed for the night, your designated driver friend nowhere to be seen, and with the only legal option to get to your house in the suburbs being a $70 Uber ride. Prime setting to chance it. No surprise then that out of the ten million or so criminal arrests that happen every year in this country, 10% are just DUIs, more than all violent crimes combined. Drunk driving is one of the most intersectional of crimes. Rich and poor alike, this is the universal criminal temptation.

When someone is arrested for drunk driving, they get handcuffed, their vehicle is towed away into the abyss, and they might spend a few hours in jail if they’re particularly unruly or the cop is in a shitty mood. When they’re released from the precinct into the cold morning hours, they’re handed a gift bag with some terrifying paperwork informing them DUIs are punishable by up to three hundred and sixty four days in jail. That’s just the statutory maximum that never (almost, we’ll get to that) gets imposed, but they don’t know that, so naturally they panic. They panic and google.

I’ve written before about how useless I am, and I am especially useless with DUI cases. DUI cases are so boring because of how straightforward they usually are. They were drunk. They were driving. And more often than not, they admitted their drinking to the cop that saw them using their car to recreate a crochet weaving pattern across multiple lanes of traffic. Despite these lopsided conditions, establishing someone’s guilt through the constitutionally-mandated public jury trial avenue remains a pain in the ass for the system — way too expensive, takes way too long, and [gasp] might not actually work if the jury doesn’t buy the government’s story. The prosecutor takes the tack of “it sure would be super if you saved us the hassle and just admitted you’re guilty.” (No, history doesn't repeat itself, why do you ask?) and they incentive this outcome with plea deal offers that are entirely within their discretion. At least ninety-four percent of defendants take them up on it.

Keeping the assembly line humming was most of our job. We negotiated plea deals in whatever crevices in the courthouse building we could spare. Sometimes the prosecutors would find a spare jury room and set up shop there with their laptops, and all the defense attorneys (private and public alike) would crowd inside and wait in line to talk about the merits of their case. The open air atmosphere inside that room was chummy, but we also would witness negotiations happening transparently in real time.

One private attorney seemed particularly attentive to his appearance, and was that day glamorously adorned with a pinstripe suit and a lumbering gold watch that seemed uncomfortably heavy. When it was Pinstripes’ turn in the pit, his pitch to the prosecutor was as succinct as the insider’s lingo could sustain: “No priors, no aggravators, and the blow is in the low teens. Negligent amendment?” The prosecutor was nodding along and flipping through their notes and pulled out a template form to memorialize the deal. No surprise given the circumstances, I could’ve secured the same deal in my sleep for any of my clients.

But if you can swap in virtually any attorney into the slot without affecting the outcome, how would any individual attorney stand out from the rest? Theoretically a private attorney can devote their craft and grind away to become the best goddamn DUI lawyer to ever roam the land, but the infinitely more efficient approach to standing out is just by dialing up the marketing. They play the search engine optimization game and dump a thesaurus’ worth of synonyms for the ”I got a DUI and I’m not poor” query to capture those panic-stricken google searches. Their billboards are conveniently located near every major highway exit, with a photo crossing their arms to showcase how hard they’ll fight the cops for you. One law firm required their attorneys to show up to court in a muscle car splattered with letters as tall as a toddler spelling out “DUI?” along with the firm’s phone number. The specter of up to three hundred and sixty four days in jail ricocheting inside a client’s head is all the sales closing you need to rack up a five to ten thousand dollar retainer. Three hours of my time as a public defender was a windfall to a private attorney lucky enough to snag a client with money.

Pricey Asymmetry

Outside of the courtroom and outside of the negotiation room, there were the hallways. The courthouse building was old enough to lack the luxury of private conference rooms, so every attorney would find an empty spot on the hallway pews to have a “confidential” meeting with their client. There was an unspoken code of honor not to eavesdrop, one which even the court marshals and deputies earnestly respected, but sometimes you can’t help but overhear.

Pinstripes came out of the negotiation room, holding that basic bitch Negligent Amendment plea offer in his hands. His client was sitting in a pew, anxiously fidgeting.

“The prosecutors gave me hell for your case, but I put those sons-of-bitches through the ringer until they caved! They’re willing to offer you that negligent reduction we talked about.”

The sigh of relief from the client felt like it was forced out by bellows. He visibly relaxed, managed to crack a smile, presumably relieved he was finally allowed to drop the emotional rucksack he’d been carting around.

A necessary throat-clearing: an attorney’s competence and commendability is not at all predicated on either their practice area or the source of their compensation. Pinstripes was a competent attorney. He delivered on effective representation, and his client was fully satisfied with the resolution. Pinstripes may have been exaggerating his own contributions, but he was under no formal obligation to notify his client of any cheaper competitors. All I point out here is how different circumstances can lead to different incentives. Mr. Monk Sleeves above had over the years whittled himself away into a finely-honed and effective apparatus, devoid of any extraneous adornments. It didn’t matter how stupid his sleeves looked, he was still going to be appointed to clients. Privately retained attorneys face a different set of incentives. They need the hand that pays to feel good about the transaction and so have every incentive to exaggerate their efforts. The fact that their client has money to pay them very likely means they’ve never been in trouble before, never needed a lawyer before, and never had to face the bore end of a judge before. The paying client is unlikely to get arrested again, and even if he did he never would attain the bird’s eye view of the system necessary to evaluate Pinstripe’s comparative utility. Classic information asymmetry.

Can money help tip the needle? Yes, of course, sometimes, and typically only when gargantuan sums are levied. OJ Simpson had the means and motivation to throw loot at objectively hopeless needle in a haystack endeavors. For DUIs, I knew of one case where the guy blew a 0.12% BAC (not that bad by my caseload’s standard) and managed to get acquitted after sinking about $20,000 to fly in three different nationally-recognized breath test experts to testify at his trial in podunk district court.

But most of the time, no. The primary benefit of money is as a paradoxical prophylactic — the fact that you have it is a very good indicator you won’t need to use it.

364 Days

I’ll end with one last story. If someone is still in jail by the first appearance hearing, the court assumes they are indigent and expects the public defender’s office to handle it unless a private attorney told them otherwise. I scanned through the dozens of cases on my jail calendar docket and quickly triaged them based on a brief skim of the docket and police reports. One guy stood out to me as uniquely fucked. It was a DUI, of course, except he was already on probation for a third DUI with the same court. Nothing within the police report raised any evidentiary red flags, this was a plain vanilla clean case as far as I could tell. I saw through the Matrix and read the green letters directly, and they spelled Doom.

Seated on the molded plastic chairs the jail uses as he wore some ill-fitting Crocs, I delivered my grim prognosis, appropriately qualified given my limited vantage point. I advised him not to bail out, as the money would vanish within the coffers of a bail bondsman and only provide a vanishingly temporary reprieve from jail. Spending several thousand dollars to be out for a few weeks didn’t seem worth it to me, but I reminded him it was his and his family’s choice to make.

The next time I saw him was in court, and he was not wearing jail scrubs with Crocs. I walked up to talk to him but before I could get a word in, he cut me off brusquely and flat-out declared he didn’t me because he had retained private counsel. All delivered with the haughty cadence that would make a Royalist blush. I shrugged and moved on to my next entry. With him having bailed out and hiring a private attorney, his expenses were steadily mounting.

What the judge eventually did with his case was highly unusual, but not at all surprising to me, given my scrying ability. He plead guilty, because of course, and the judge was so fed up with his repeat offenses that she didn’t even bother giving him a probation period to right his wrongs, just imposed and closed. He was sentenced to the maximum three-hundred and sixty four days, to this day the only time I ever saw it happen. His lawyer could’ve been a pillow and nothing would have been different.

I must confess schadenfreude. Despite my own feelings about the carceral state, someone else’s liberty is a small price to pay for gratifying my own ego and affirming my prognostications.

If you’re in trouble with the law, do your best to qualify for a public defender. They may not always have pinstripes, but they know the system and the players inside and out. The Constitution guarantees your right to change your mind at any point after, but there’s no harm in test-driving the budget option first. You might get to the same destination, just with a lot more money in your wallet.

I made this up.

The number of methodological issues inherent in comparing public defenders and private attorneys is way too long to get into here.

For those who are curious, this is me. I got my start working for a public agency but then opened my own private practice. So I’m technically a private attorney, but one whose caseload is 100% indigent defense. It’s much simpler and still accurate to just call myself a public defender, and no I will not change my Tinder bio.

Fantastic stuff. I would read a whole book like this. Always a pleasure to learn about the little details and rituals of these complex, historical, massively materially significant, and tbh mostly opaque (to me, an outsider, despite having many lawyer family/friends) processes and organizations.

One angle I enjoy thinking about is how similar patterns also exist in "private" organizations, but with some notable differences. Don't have specifics now but may add some later.

When I was an investigator for a private firm I was always surprised at how many DUI cases I got, mostly because there isn't much to investigate. You just check the stop location for uneven pavement and maybe FOIA the arresting officer, that's about it. Of course it later came out that the cops had been miscalibrating their Breathalyzers and a few dozen cases got dismissed, so you never know! Anyways, always enjoy these peeks behind the curtain--not many PDs talk openly about the mundane realities of criminal defense, so it's always nice to see that side acknowledged. Not every day can be springing a guy from death row, after all. And if you ever need a P.I. in LA, hit me up.