Scott Alexander’s Noncentral Fallacy, dubbed “the worst argument in the world”, is a classic example of manipulative rhetoric. The basic structure of this fallacy, as Scott describes it, is to apply technically correct labeling in order to conjure up misleading connotations — say by labeling MLK a “criminal” in order to obliquely undermine his legacy. Scott is identifying an important and pervasive dynamic, but he’s misidentifying why it’s a problem because the concept of “centrality” is both incoherent and irrelevant. Rather, the real issue is how debates over categorizations and labels get utilized as a fallacious shortcut to avoid having to debate some Other Thing. Let’s call it the “Sticker Shortcut Fallacy” instead.

What even is centrality?

Honed down to its most discrete point in semantic space, the barest definition of criminal is “anyone who has ever broken any law”. While the word certainly shoulders a constellation of emotionally salient connotations, these are heavily susceptible to context and priming, and very often vehemently disagreed with. Which archetypical avatar of criminality gets conjured up in your mind will depend on your particular background, the specific narrative presented to you, as well as whatever sympathies you may hold.

Al Capone might be the prototypical criminal in people’s minds, but on paper, he’s actually just a tax evader. Robin Hood literally stole money from people, but he gave it to the poor, so his legacy tends to be that of a folk hero rather than a felon. Based on the severity of punishment, nothing compares to the legally sanctioned torturous spectacle of drawing and quartering those convicted of high treason, but whether such a person is a quote-unquote criminal depends on which side you’re on. The Founding Fathers were unambiguous seditious conspirators against the greatest empire of their time, yet no one — except perhaps some nostalgic British monarchists — thinks of them as criminals for this.1 How exactly do you adjudicate which one is a “central” archetype of criminal, and who decides?

The disagreement over centrality applies to other examples cited by Scott, especially when you jettison the semantic baggage and start with a blank slate. The core essence of theft might be “taking other people’s property without their consent” but depending on the context, different examples will herald primacy. For instance, if you’re a record company, it might be illegal downloads. If you’re an overlooked office worker, it might be someone else taking credit for your achievements. If you’re a 19th century anarchist, it might be the entire concept of land property. If you’re a white college student afraid of putting on a sombrero, it might be cultural appropriation. Who decides which example should take primacy?

This isn’t a navel-gazing exercise when the answer to the question controls the boundaries of fallacious reasoning, but this endeavor dredges up the same tediously familiar and intractable disputes over whether cereal is a soup, or if liquids can themselves be “wet”. Do we look up the dictionary? Do we consult linguists? Do we conduct a general population survey? Of whom? Orchestrating a consensus on simple definitions is already difficult enough, but adjudicating agreement on which archetypes should be central is beyond hopeless.

Consider Scott’s description of the Noncentral Fallacy again:

I declare the Worst Argument In The World to be this: "X is in a category whose archetypal member gives us a certain emotional reaction. Therefore, we should apply that emotional reaction to X, even though it is not a central category member."

No one who engages in the Worst Argument will ever ever ever concede the bolded clause, because doing so completely nullifies their attempted sophistry! Since no one will hand you the refutation key so transparently, this will inevitably invite all sorts of question begging: “Your argument is fallacious because X is not a central category member. And it’s not a central category member because…I say so?”

More central is not less fallacious

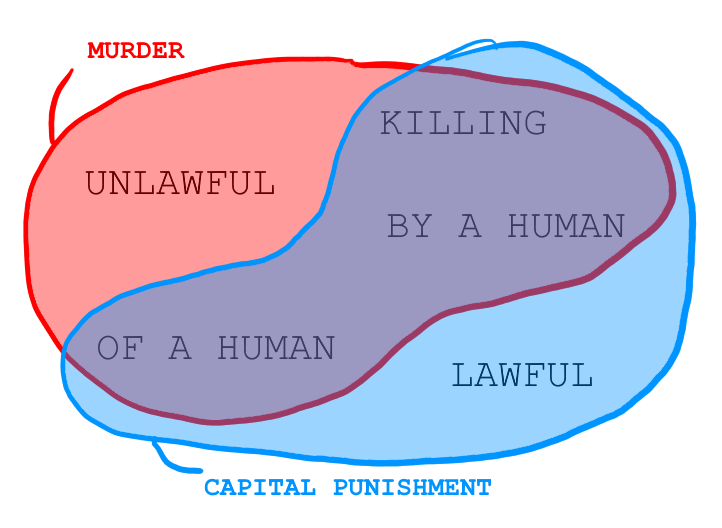

I'm going to assume the above away and just pluck central archetypes based on colloquial understanding to show that the Noncentral Fallacy remains the wrong prism. The barest, narrowest, and most widely accepted understanding of murder involves the basic ingredients of 1) the unlawful 2) killing 3) of a human being 4) by another.2

With capital punishment, the only missing ingredient is whether the killing is unlawful (or illegal, illicit, or somehow unauthorized) which is a very peculiar state of affairs for a state-sanctioned execution. Accordingly, anyone insisting that capital punishment is murder is transparently agitating for the unlawful clause to be swallowed whole without resistance. They’re hoping that slapping the murder sticker on the conduct provides them with a shortcut to avoid direct, substantive argumentation. Hence, the Sticker Shortcut Fallacy.

The essential conditions for this type of fallacy are:

The premise you're ultimately after is either very difficult to substantiate or is highly contested. (e.g. capital punishment should be unlawful)

There's another adjacent premise that is much easier to establish or is otherwise pedestrian. (e.g. murder should be unlawful)

Both premises share an overlapping semantic cluster, a set of related concepts or connotations, that can be used to blur the lines between the two.

Since everyone loves illustrations, this is one way to visualize it:

The only way to accept the murder sticker is by adopting the unlawful premise and abandoning the lawful premise. In the case of “abortion is murder”, this cheap trick performs a lot of heavy lifting because insisting on the specific vocabulary is an attempt to surreptitiously assert “fetuses should be considered human beings” and “the killing of fetuses should be unlawful”, all without having to do the very hard work of substantiating either premise, or maybe just hoping you won't notice.3

This demonstrates that the Sticker Shortcut Fallacy is fundamentally a snuck premises or presuppositions fallacy, one that is unlikely to happen inadvertently given the level of intentionality required. What might initially seem like a harmless categorization game of ‘which dishes go into which cupboard?’ is actually a subtle way of shifting someone's stance by altering the foundation of their argument.

Scott Alexander was very close to properly identifying the Sticker Shortcut Fallacy in an earlier post called Diseased thinking: dissolving questions about disease:

People commonly debate whether social and mental conditions are real diseases. This masquerades as a medical question, but its implications are mainly social and ethical. We use the concept of disease to decide who gets sympathy, who gets blame, and who gets treatment.

This is exactly right. A premise such as “individuals who are addicted to drugs deserve our sympathy and should receive medical treatment” is bound to be hotly contested and difficult to substantiate, whereas if you just slap the disease sticker on addiction then you can assume away the hard work. The reason this fallacy is so pervasive and noxious is because its distraction potency is extremely high. It is very easy to get hoodwinked and dive right into debating that “capital punishment is the good kind of murder”, a quagmire no one can cleanly escape from. If someone tacitly accepts the sticker, there's a chance they won’t realize they’ve left the gate open for the presuppositions to slink in, hopefully not until it's too late.

The only effective response when someone is deadset on a categorization question is to directly ask why the categorization matters. What information or insight, if any, is gleaned from answering the question? There are actually valid purposes to these types of semantic arguments, perhaps when examining the extent language influences its speakers’ worldview, or when someone wants to draw attention to similarities between categories that may otherwise get drowned out.

But if someone is using the Sticker Shortcut Fallacy to mislead, to sleepwalk others into compliance, their efforts would be very effectively neutered because they would now required to expose the implied connotations they were hoping others would make by adopting the label. If they resist answering such a simple question, that’s also its own kind of answer.

Many thanks to Trembling Mad for helping me crystalize this concept.

Ironically, they ensured that the only crime specifically mentioned in the Constitution was treason. Talk about pulling up the drawbridge behind you.

This is why when a lion eats someone, we don't use murder even though a human was definitely killed. Do lions even respect the law? A question for another time perhaps.

Its sister slogan “meat is murder” performs similar presupposition heavy lifting on whether animals should be considered to have the same moral weight as humans, and whether their killing should be unlawful.

And interestingly Scott’s most recent post about “genetic inferiority” is this same concept. Trying to “sticker shortcut” the idea that “genetic inferiority” is a moral judgement, and therefore suspiciously Nazi-like, when it’s often just a practical judgement.

Very nice post. I'm already really enjoying your new "write fast, break tihngs" approach. Looking forward to more essays!